sulla stampa

08 gennaio 2014

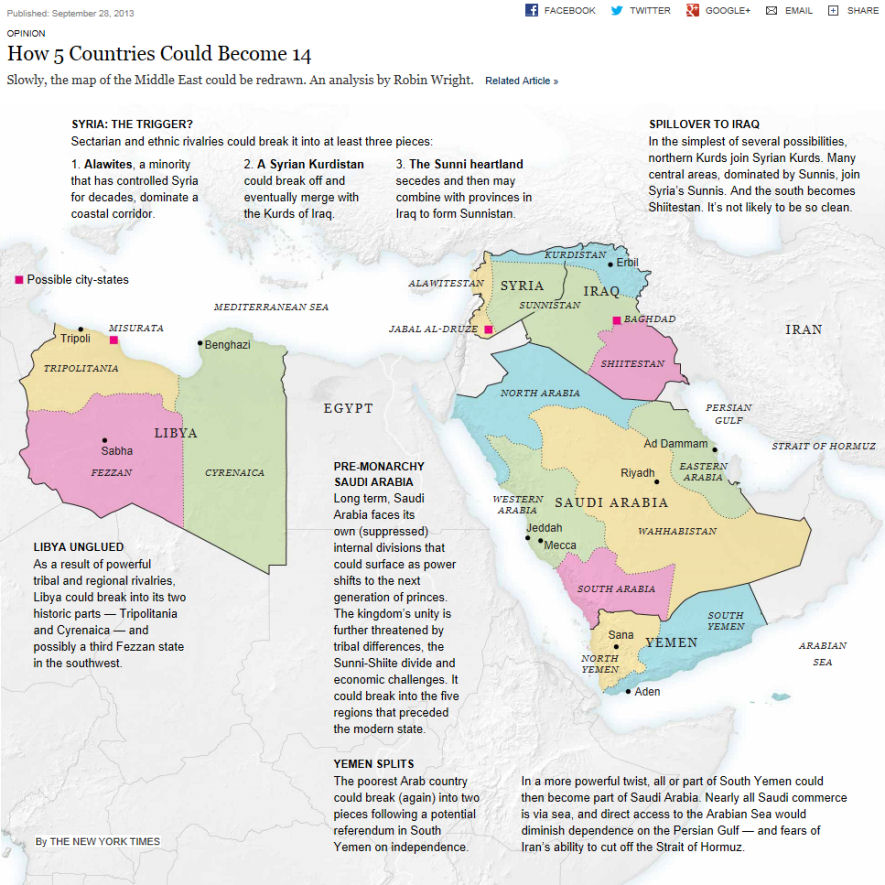

La mappa del Medio Oriente secondo religioni ed etnie

Se cancellassimo i confini disegnati in epoca coloniale, da 5 stati attuali ne uscirebbero 14

su LINKIESTA

|

| La mappa costruita dal New York Times Vedi anche “Lo Stato Islamico dell'Iraq” Enrico Mentana su Facebook |

La mappa attuale del Medio Oriente, perno politico ed economico dell'ordine internazionale, è a brandelli. La rovinosa guerra siriana è il punto di svolta. Tuttavia, le forze centrifughe delle credenze tribali ed etniche – rafforzate da conseguenze non volute delle Primavere arabe – contribuiscono a fare a pezzi una regione delineata dal potere coloniale europeo un secolo fa e difesa fin da quel momento dagli autocrati arabi.

Una mappatura diversa dell'area sarebbe un elemento strategico di cambiamento, capace potenzialmente di riconfigurare le alleanze, le sfide legate alla sicurezza, i commerci e i flussi di energia per gran parte del mondo.

La posizione di primo piano della Siria la rendono un centro strategico per il Medio Oriente. Ma è un Paese complesso, ricco di varietà etnica e religiosa, quindi fragile. Dopo l'indipendenza, la Siria ha subito più di una mezza dozzina di colpi di Stato tra il 1949 e il 1970, anno in cui la dinastia degli Assad ha preso il pieno potere.

Ora, dopo 30 mesi di massacri, la diversità interna si è rivelata fatale, uccidendo sia le persone che il Paese. La Siria si è sbriciolata in tre regioni ben identificabili, ciascuna con la sua bandiera e il suo corpo militare. Un futuro diverso sta prendendo forma: uno staterello stretto lungo un corridoio che corre dal Sud, attraversa Damasco, Homs e Hama fino alla costa Nord del Mediterraneo è controllato dalla setta degli Alauiti, la minoranza che fa capo ad Assad. Nel Nord, c'è il piccolo Kurdistan, ampiamente autonomo da metà 2012. La parte più ampia è il cuore del Paese, dominata dai sunniti. La questione siriana costituirà un precedente nella regione, a partire dal suo vicino. Finora, l'Iraq ha resistito al crollo a causa della pressione straniera, del timore di ritrovarsi solo nella regione e le riserve di petrolio che gli hanno portato lealtà, almeno sulla carta. Ma ora la Siria sta risucchiando l'Iraq nel suo vortice.

«I campi di battaglia si stanno unendo», ha avvisato l'Inviato delle Nazioni Unite Martin Kobler a luglio. «L'Iraq è la faglia tra il mondo sciita e sunnita e tutto ciò che accade in Siria, chiaramente, ha ripercussioni sullo scenario politico iracheno». Col tempo, la minoranza sunnita irachena – specialmente nella provincia occidentale di Anbar, luogo di proteste antigovernative – potrebbe provare maggiore comunanza con la maggioranza sunnita siriana dei territori a Est. I legami tribali e i scambi di merci attraversano il confine. Insieme, potrebbero formare un Sunnistan. Il sud dell'Iraq diventerebbe di fatto uno Shiitestan, anche se la divisione non sarebbe probabilmente così netta.

I partiti politici dominanti nelle due regioni curde della Siria e dell'Iraq hanno differenze che durano da tempo, ma quando il confine è stato aperto, lo scorso agosto, più di 50 mila curdi siriani sono fuggiti nel Kurdistan iracheno, creando nuove comunità transnazionali. Massoud Barzani, presidente del Kurdistan iracheno, ha poi annunciato il progetto del primo meeting di 600 curdi provenienti da 40 partiti di Iraq, Siria, Turchia e Iran per questo autunno.

«Sentiamo che ora ci sono le condizioni giuste», ha dichiarato Kamal Kirkuki, l'ex speaker del Parlamento del Kurdistan iracheno, a proposito del tentativo di mobilitare curdi dispersi in più regioni per discutere del loro futuro.

ll seguito sul New York Times

Outsiders have long gamed the Middle East: What if the Ottoman Empire hadn't been divvied up by outsiders after World War I? Or the map reflected geographic realities or identities? Reconfigured maps infuriated Arabs who suspected foreign plots to divide and weaken them all over again.

I had never been a map gamer. I lived in Lebanon during the 15-year civil war and thought it could survive splits among 18 sects. I also didn't think Iraq would splinter during its nastiest fighting in 2006-7. But twin triggers changed my thinking.

The Arab Spring was the kindling. Arabs not only wanted to oust dictators, they wanted power decentralized to reflect local identity or rights to resources. Syria then set the match to itself and conventional wisdom about geography.

New borders may be drawn in disparate, and potentially chaotic, ways. Countries could unravel through phases of federation, soft partition or autonomy, ending in geographic divorce.

Libya's uprising was partly against the rule of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi. But it also reflected Benghazi's quest to separate from domineering Tripoli. Tribes differ. Tripolitanians look to the Maghreb, or western Islamic world, while Cyrenaicans look to the Mashriq, or eastern Islamic world. Plus, the capital hogs oil revenues, even though the east supplies 80 percent of it.

So Libya could devolve into two or even three pieces. The Cyrenaica National Council in eastern Libya declared autonomy in June. Southern Fezzan also has separate tribal and geographic identities. More Sahelian than North African in culture, tribes and identity, it could split off too.

Other states lacking a sense of common good or identity, the political glue, are vulnerable, particularly budding democracies straining to accommodate disparate constituencies with new expectations.

After ousting its longtime dictator, Yemen launched a fitful National Dialogue in March to hash out a new order. But in a country long rived by a northern rebellion and southern separatists, enduring success may depend on embracing the idea of federation — and promises to let the south vote on secession.

A new map might get even more intriguing. Arabs are abuzz about part of South Yemen's eventually merging with Saudi Arabia. Most southerners are Sunni, as is most of Saudi Arabia; many have family in the kingdom. The poorest Arabs, Yemenis could benefit from Saudi riches. In turn, Saudis would gain access to the Arabian Sea for trade, diminishing dependence on the Persian Gulf and fear of Iran's virtual control over the Strait of Hormuz.

The most fantastical ideas involve the Balkanization of Saudi Arabia, already in the third iteration of a country that merged rival tribes by force under rigid Wahhabi Islam. The kingdom seems physically secured in glass high-rises and eight-lane highways, but it still has disparate cultures, distinct tribal identities and tensions between a Sunni majority and a Shiite minority, notably in the oil-rich east.

Social strains are deepening from rampant corruption and about 30 percent youth unemployment in a self-indulgent country that may have to import oil in two decades. As the monarchy moves to a new generation, the House of Saud will almost have to create a new ruling family from thousands of princes, a contentious process.

Other changes may be de facto. City-states — oases of multiple identities like Baghdad, well-armed enclaves like Misurata, Libya's third largest city, or homogeneous zones like Jabal al-Druze in southern Syria — might make a comeback, even if technically inside countries.

A century after the British adventurer-cum-diplomat Sir Mark Sykes and the French envoy François Georges-Picot carved up the region, nationalism is rooted in varying degrees in countries initially defined by imperial tastes and trade rather than logic. The question now is whether nationalism is stronger than older sources of identity during conflict or tough transitions.

Syrians like to claim that nationalism will prevail whenever the war ends. The problem is that Syria now has multiple nationalisms. “Cleansing” is a growing problem. And guns exacerbate differences. Sectarian strife generally is now territorializing the split between Sunnis and Shiites in ways not seen in the modern Middle East.

But other factors could keep the Middle East from fraying — good governance, decent services and security, fair justice, jobs and equitably shared resources, or even a common enemy. Countries are effectively mini-alliances. But those factors seem far off in the Arab world. And the longer Syria's war rages on, the greater the instability and dangers for the whole region.

![]() 08 gennaio 2014

08 gennaio 2014